Build, Baby, Build.

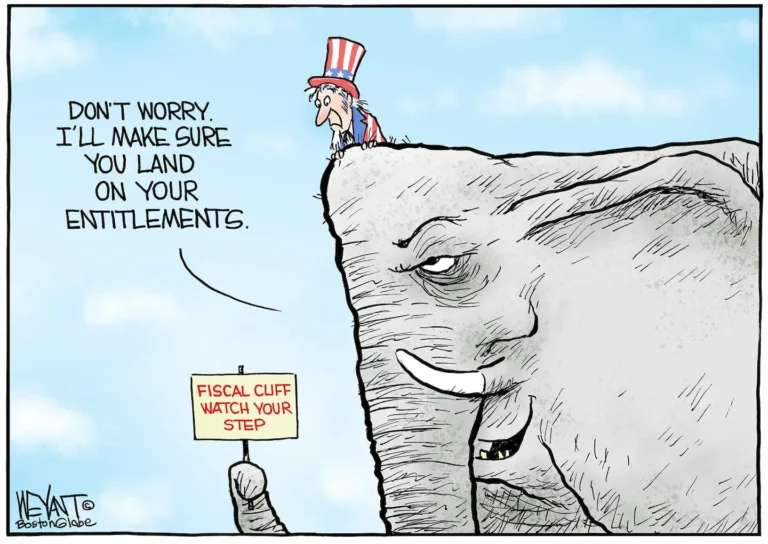

Housing policy in the United States is terrible. We know it isn’t good. We feel it isn’t good. It caused a global crisis just 16 short years ago. Young people across the nation are feeling the pinch in housing. Housing costs are up dramatically. Monthly CPI reports consistently show that shelter costs remain the most inflationary aspect of the economy, especially in urban areas. States’ unwillingness (or policy-induced inability) to create affordable housing has hindered our economy. Young people are living at home longer, people are moving in with roommates to save on costs, homelessness in urban areas is out of control, and our most significant metropolitan areas are struggling to grow as a result of failed housing policy. The short and simple takeaway is that something is wrong with housing. The Covid-19 pandemic and its lingering economic effects have demonstrated this.

It doesn’t have to be this way. The “Yes in my backyard ” movement, or YIMBYs for shorthand, has been hard at work at the local, State, and Federal levels bringing about housing policy change. The core principle of this movement is the deregulation of housing construction and zoning policy and the building, baby, build. In a few simple concepts for the economics folks in the back, the answer to rising housing/rental/shelter costs is increasing the supply. We need to increase the supply dramatically. There are plenty of examples in which the primary determining factor of housing costs is a simple supply/demand issue.

With rent prices outpacing income growth in many urban areas, millions of Americans are burdened by high housing costs. According to the National Low Income Housing Coalition, in 2021, a full-time worker needed to earn $24.90 per hour to afford a modest two-bedroom rental home at fair market rent. This is an unsustainable trajectory for the United States.

Policy Proposals to Sustainably Reduce Housing Costs

Increasing Housing Supply Through Zoning Reforms

In expanding zoning for multi-family units, we can directly increase housing availability. Restrictive zoning laws have been a significant barrier to meeting housing demand (see California). Zoning laws often constrain and limit the ability of developers to build homes either A. affordably or B. densely. A 2020 National Bureau of Economic Research study found that zoning restrictions have increased housing costs by up to 50% in major cities like New York and San Francisco. This is where we begin to understand the pattern of major suburban sprawls in San Francisco. (hideous and inefficient.) These restrictions curtail the number of units that can be constructed, decreasing supply and increasing prices due to intensified competition for scarce housing space. By improving these laws, cities can unlock the potential for new developments, leading to a significant increase in housing supply. This expansion helps to alleviate the pressure on the housing market, making it easier for people to find affordable places to live. By unlocking the ability to increase supply, market forces should do what they do best: stabilize and normalize.

An increased housing supply has a direct correlation with rent prices. The Urban Institute reports that a 10% increase in housing stock can lead to a 1-2% decrease in rents. While this percentage might seem insignificant, it can translate into substantial savings for renters. For example, in a city where the average monthly rent is $2,000, a 1% decrease equates to $20 in monthly savings or $240 annually. Moreover, these savings are particularly impactful for low- and middle-income households, for whom rent comprises a more significant portion of their monthly expenses. Lowering rent prices improves affordability, allowing inhabitants to distribute more of their earnings toward other needs like healthcare, education, investments, spending, or savings. By allowing more of our paychecks to invest in different aspects, we can ideally see growth in the overall macro economy, more vital consumers on the micro level, and less financial burden from a psychological standpoint on the individual. A 3 birds one stone type situation…

In 2018, Minneapolis made a groundbreaking decision by adopting the Minneapolis 2040 Plan, becoming the first major U.S. city to eliminate single-family zoning citywide. (another Minneapolis win.) This policy change allows for constructing duplexes and triplexes in all residential areas, effectively increasing the potential housing density throughout the city. Following the zoning reform, there was a 30% increase in applications for multi-family housing units in 2019. This surge indicates a strong reaction from developers eager to build more housing, signaling that zoning laws were a significant bottleneck in housing production. (Market forces at work baby) By permitting duplexes and triplexes, the city enabled a broader range of housing types to meet the diverse needs of its residents. On a more superficial level, introducing varied housing types allows for rapid density shifts, allowing more housing per square inch, thus increasing the available shelter. This diversification is crucial for accommodating different family sizes, income levels, and lifestyle preferences. Allowing higher-density housing in all neighborhoods promotes inclusivity and provides opportunities for more residents to access amenities and services previously limited to certain areas. Although critics often see this as an assault on suburbia and our accustomed lifestyles think of families with different sizes; single-parent households with one child don’t need a four-bedroom townhouse, or income-constrained college students don’t need massive spaces since the unit is essentially just a place to eat, sleep, and shower. Now, onto the essential bits in case you were getting bored already… PRICES.

Although it’s too early to measure the long-term impact on rent prices, the increase in housing applications suggests that supply will grow, which is expected to contribute to rent stabilization or reduction over time. As of 2024, the Twin Cities were among the first to tame inflation, getting their annualized rate under the FED’s goal of 2% to 1.8% in August of 2023…juxtaposed with the national rate of 3.7% at that time, while housing proved to be one of the most stubborn components of the report. Minneapolis’s proactive approach has inspired other cities to consider similar zoning reforms, signaling a potential shift in national housing policy trends. Reforming zoning laws to allow higher-density housing is a powerful tool for cities grappling with housing affordability crises. By increasing the supply of housing units, cities can mitigate the upward pressure on rents caused by high demand and limited availability. The example of Minneapolis demonstrates the tangible benefits and feasibility of such reforms. Increased applications for multi-family housing developments indicate that developers are ready to respond to housing needs when given the opportunity.

Zoning reform can help address social equity issues by promoting diverse and inclusive communities. A significant increase in housing supply can lead to measurable rent decreases, improving residents’ affordability. Zoning reforms can contribute to more equitable neighborhoods by providing diverse housing options accessible to various income levels. The success of Minneapolis’s approach offers a viable model for other cities to emulate, potentially amplifying the impact on a national scale. Implementing zoning reforms requires careful planning, community engagement, and consideration of local contexts. However, the conceivable benefits of housing affordability and social equity make it a compelling strategy for policymakers seeking sustainable solutions to the housing crisis.

Increase funding for affordable housing programs in grants and tax credits.

Expanding the Low-Income Housing Tax Credit (LIHTC) incentive can significantly reduce housing costs by increasing the supply of affordable housing and making rents more accessible for low- and moderate-income families. Although increasing tax credits and grants typically subsidize demand, the associated supply increase could create a more sustained housing growth cycle if paired with the associated supply increase. By incentivizing the construction of affordable units through grants and tax credits to local and State governments, affordable unit construction can be supercharged.

Established in 1986, the LIHTC is a federal program encouraging private investment in developing and rehabilitating affordable rental housing. Developers receive tax credits in exchange for committing to reserve a portion of their units for low-income tenants at restricted rents for at least 30 years. Increasing the allocation of these tax credits allows more affordable housing projects to be financed, directly boosting the supply of affordable units. Creating the incentive structure for affordable housing policy could prove paramount to constructing the needed units. This public-money-private industry coalition has proven successful regarding microchip industrial policy. Thus, it is worth attempting in the housing sector.

This increase in supply helps balance the housing market by reducing competition for existing units, which can lead to lower rents in both LIHTC and market-rate properties. The National Council of State Housing Agencies reports that LIHTC has financed over 3 million affordable housing units since its inception. Expanding the program by 50% could result in an additional 400,000 affordable units over ten years, according to Affordable Housing Credit Improvement Act estimates. Studies by the Urban Institute indicate that a 10% increase in the supply of affordable housing can lead to a 1% to 2% decrease in overall rents, demonstrating the direct impact on housing costs.

Moreover, expanding LIHTC lowers development costs for builders by reducing reliance on debt financing, allowing savings to be passed on to tenants through lower rents. The National Association of Home Builders notes that LIHTC properties can experience development cost reductions of up to 20% compared to projects without such incentives. The program also stimulates economic activity by creating jobs in construction and related industries, which can lead to higher income levels and make housing more affordable relative to income. For every 100 units developed, approximately 120 jobs are created, generating $7.9 million in wage income and $2.2 million in taxes and revenue for local governments.

Expanding LIHTC also addresses housing needs in underserved areas by allowing for more significant investment in rural and underserved urban regions, thereby reducing local rents and preventing displacement. Additionally, it encourages the development of mixed-income communities, promoting socioeconomic diversity and stabilizing housing markets by ensuring consistent demand across different income brackets. Legislative proposals like the Affordable Housing Credit Improvement Act aim to expand LIHTC allocations by 50%, simplify program requirements, and enhance the credit’s effectiveness. Maximizing the impact of a LIHTC expansion involves targeting high-need areas, extending affordability periods, and leveraging additional funding through other programs and state and local support. Addressing challenges such as rising development costs and ensuring equity and inclusion are essential for the success of LIHTC expansion.

In conclusion, expanding the Low-Income Housing Tax Credit incentive is a proven strategy for reducing housing costs and increasing affordability nationwide. LIHTC directly addresses the supply-side constraints contributing to high housing costs by incentivizing private investment in affordable housing. The evidence demonstrates that LIHTC expansion can increase affordable housing supply, stimulate economic growth, promote inclusive community development, and ensure long-term affordability for low-income households.

Encouraging and Expanding Accessory Dwelling Units.

Accessory Dwelling Units (ADUs), such as backyard cottages or basement apartments, promote lower rents and contribute to rent deflation by increasing the housing supply within existing neighborhoods. These come into fruition around California, often dubbed the Grandma unit. By utilizing underused spaces on residential properties, ADUs add affordable rental units without requiring extensive new developments, easing the demand pressures that drive up rents. Although not nearly as effective as denser units, utilizing existing spaces and identifying existing properties is paramount to housing success.

Simplifying regulations around ADUs leads to a significant rise in their construction. After California passed laws in 2017 to streamline ADU approvals (SB 1069 and AB 2299), Los Angeles saw ADU permit applications soar from 117 in 2016 to over 5,000 in 2018. This surge added thousands of new rental units to the market in a short period. ADUs typically offer smaller, more affordable rental options than traditional housing units. Their lower construction and maintenance costs allow landlords to charge reduced rents, making them accessible to low- and middle-income tenants.

By increasing the number of rental units in a neighborhood, ADUs help alleviate competition for housing. The University of California, Berkeley’s Terner Center for Housing Innovation found that neighborhoods with higher ADU adoption experienced slower rent growth, indicating that even modest supply increases can dampen rent escalation. ADUs optimize existing residential land without significantly altering neighborhood character. They increase density subtly, which can cumulatively have a substantial impact on housing availability and affordability.

ADUs also have economic and community benefits. They provide homeowners with additional income streams, which can help them cover mortgages and property taxes, potentially preventing foreclosures and stabilizing neighborhoods. Since ADUs utilize existing infrastructure, they require fewer public resources than new housing developments, making them a cost-effective solution for cities facing housing shortages.

Policy considerations are crucial for promoting ADU development. Cities that have reduced barriers to ADU construction—such as lowering fees, relaxing zoning restrictions, and providing standardized building plans—have seen more excellent adoption rates. For example, Portland, Oregon, waived system development charges for ADUs, leading to a substantial increase in their construction. Encouraging ADU development can be scaled across municipalities to contribute to broader rent deflation collectively. When adopted widely, ADUs can significantly expand the affordable housing stock.

In conclusion, by promoting the development of ADUs, policymakers can effectively increase the supply of affordable rental housing, leading to lower rents and mitigating the factors that contribute to rent inflation. The experiences of cities that have embraced ADUs demonstrate their potential as a practical tool for addressing housing affordability challenges.

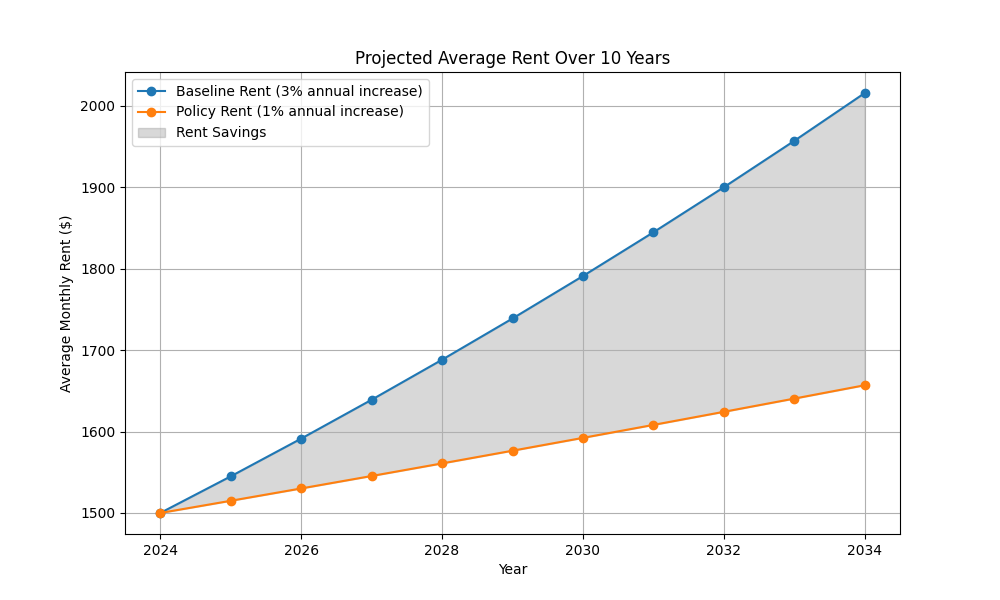

Suppose we assume a Baseline Rent increase of 3% annually starting this year, in which average rents hover around ~1500. In that case, we can project that over the next ten years, if the policy mentioned above is implemented, we can control Rent increases to roughly 1% annually, likely keeping it below what is expected to be ~2 inflation YOY.

This slows the growth rate dramatically, saving the average American hundreds of dollars monthly on expected rent increases.

Addressing the housing affordability crisis in the United States requires a multifaceted approach that includes increasing the housing supply, implementing supportive policies, and encouraging public and private sector participation. The data and real-world examples demonstrate that these strategies can lead to significant reductions in rent, improved affordability, and enhanced housing stability.

The U.S. can move towards sustainable rent by adopting zoning reforms, increasing investment in affordable housing, rent control with safeguards, and promoting diverse housing models. This would alleviate the financial burden on millions of Americans and contribute to more equitable and vibrant communities. By fixing our housing crisis, we can stimulate our economy, create more jobs, increase wealth for all Americans, and build a better America. To that, I say, Yes, in my backyard, please.